The capture of a moment has occupied the human mind for eons. First attempts can still be seen in ancient cave drawings depicting the hunting of animals and other important moments. True photography is too complicated to develop for now. And the time will come for photography to make its comeback but not now.

Camera obscura

Camera obscura is the best next thing to real photography. Before proceeding find a good sketch artist.

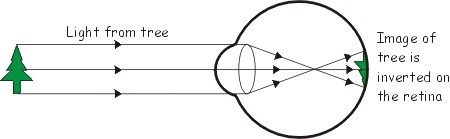

Light, being the stubborn thing it is, insists on traveling in a straight line. This is all well and good until it encounters an obstacle with a tiny opening—like a pinhole—where only a select few light paths are granted passage. These privileged rays continue on their straight-line paths, but because they have been filtered through such a narrow gap, something strange happens: the image they carry gets flipped upside down.

Now, you might wonder why this phenomenon isn’t something we constantly notice in our daily lives. The short answer? You do. All the time. Your own eyes are walking, talking (well, seeing) camera obscuras. The light entering your pupils follows the same principle: only certain rays make it through, and the image that forms on your retina is, in fact, inverted. Your brain, being the impressive data processor that it is, takes this mess of upside-down visuals and flips them right-side up before you even realize what’s happening. If your brain ever decided to stop correcting for this, well, let’s just say walking would become a very interesting challenge.

But why doesn’t this effect happen with, say, regular windows? If a tiny hole can project a reversed image, shouldn’t your living room be filled with eerie upside-down reflections of the outside world? The reason is simple: a pinhole admits only a limited number of light paths, keeping the image sharp and orderly. A window, on the other hand, is an open invitation to light from all directions. Instead of forming a crisp, reversed projection, all the incoming rays mix in a chaotic light free-for-all. The result? No clear image, just a general illumination that we call daylight.

If you ever doubt this, you can put it to the test. Take a piece of cardboard, punch a small hole in it, and hold it up in a dark room facing a bright scene. Give your eyes a moment, and you’ll see a faint, upside-down projection forming on the opposite side. This is the principle that old pinhole cameras use—an elegant, no-lens-required method of image formation that has been known since ancient times, or just around the time in which you find yourself.

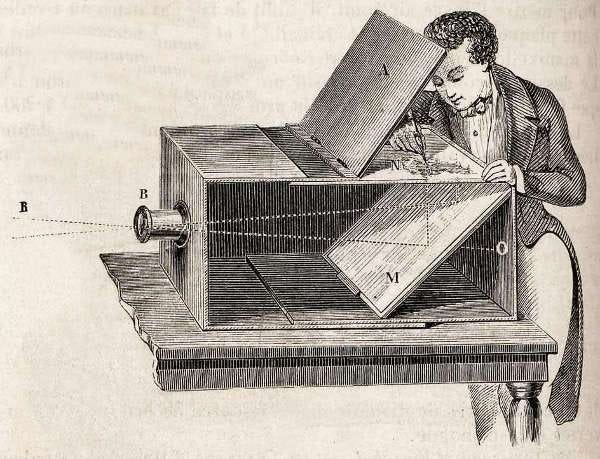

Camera obscura consists of a room or a box with a small hole in one wall facing a well-lit object or panorama on a sunny day. As the hole through which light enters is so small the image is very dim as not much light can enter. This can be fixed by increasing the hole size but then the image gets blurred. The solution to this is to use a biconvex lens that allows more light to be focused.

If a large dark room is too much of a hassle you can use this approach:

The hole can now be the size of the lens and if put inside a tube with the ability to move back and forward it will have the ability to shift focus from near to far object and vice versa.

To correct the orientation of an image a prism is used. A prism is a piece of glass polished in the shape of a, ah, prism. One could be used if only upside down is an issue but a second one is needed if true representation of the outside world is needed. The interesting part is that if you have enough bright images you can do the reverse and use this setup to project an image, just think of the overhead projector some of you still remember from school.

Camera lucida

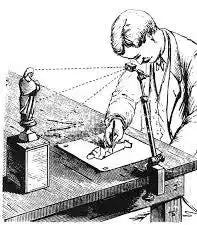

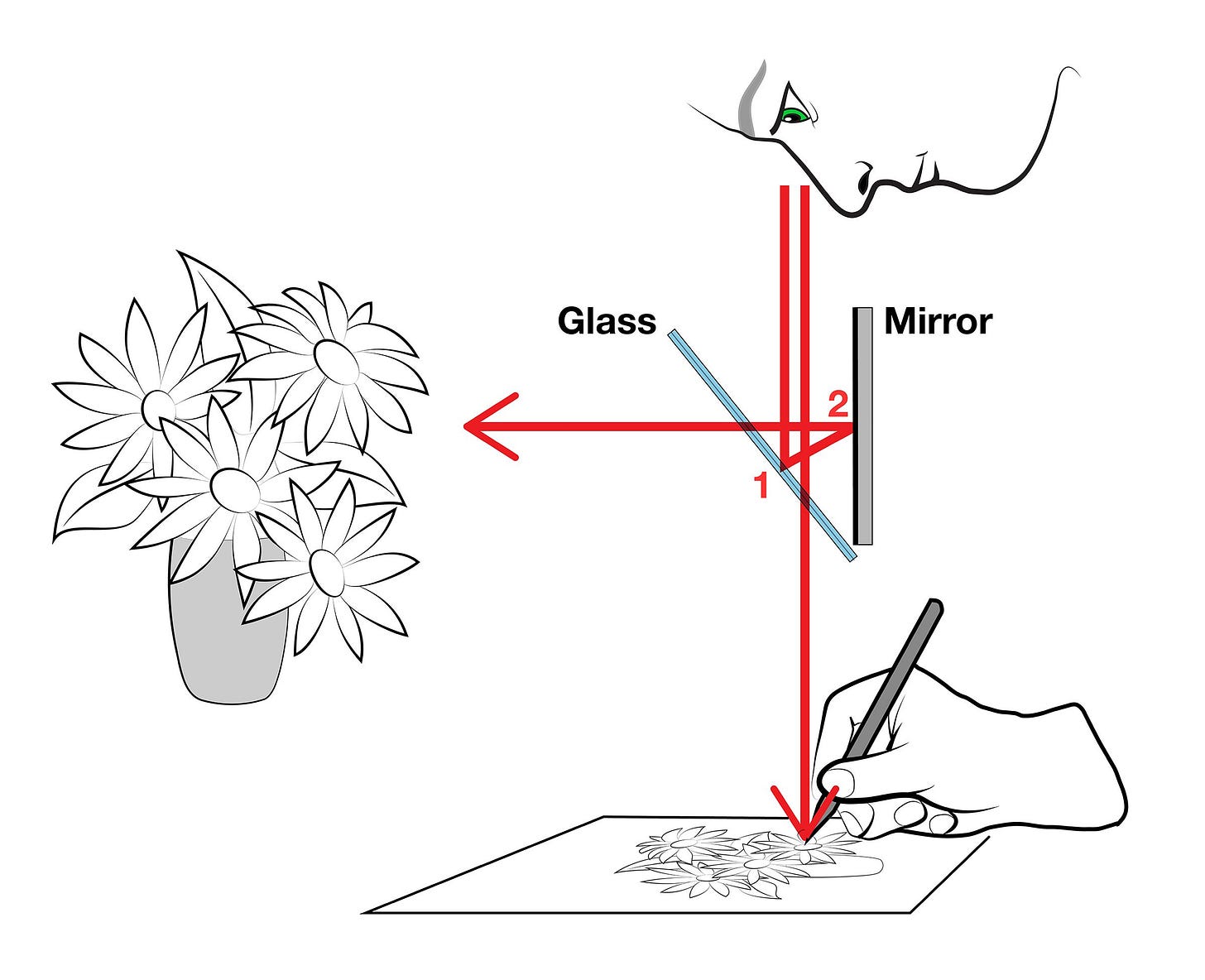

The only thing camera lucida has in common with camera obscura is the camera part of its name. Compared to camera obscura this is not a camera as we think of it. Actual camera in Latin means room and with camera lucida there is no need for a room.

What we have here is another example of prism. In this case, it is placed close to the eye so we still see the image in front of us together with the reflected image.

The combined image looks like the reflected image now occupies the same space that we see in front of us. This method was very popular with artists when they did portraits as they could actually see the image of the person they were doing the portrait of displayed on the paper and then just traced it on.